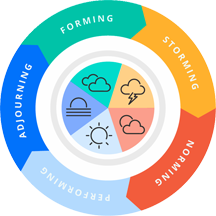

Tuckman's stages of small group development. Time spent in stages other than Performing is likely to defer accomplishing the group's task. That's why any factors that draw group members' attention away from the task or group development can be very costly indeed. This is the 1977 version of the development sequence, in which Tuckman and Jensen appended the Adjourning stage to the original four stages Tuckman hypothesized. Although this diagram seems to imply an endless loop of orderly passage through the five stages, and although that can happen, there are many possible paths through the stages of development. Image (cc) Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license by DovileMi, courtesy Wikimedia.

Especially in larger task-oriented work groups working on the more complex tasks, subgrouping is the practice of forming a subgroup of the larger group in order to complete a subtask of the larger task. In task-oriented work groups, subgrouping is often driven by a combination of task demands and access to personnel. Some examples of factors influencing subgroup formation:

- The subtask might require special knowledge that only a few people have

- Completing the subtask might require special equipment or software that's available in only limited numbers

- The subgroup might be a unit of an independent enterprise acting as a contractor or subcontractor to the organization hosting the larger group

- The organization might designate the subgroup's members so as to avoid impractical combinations of time zones

- The roster of the subgroup might be designed to ensure that the people who worked on an earlier version of the subtask would be well represented

- A more dysfunctional example (of the many): Person A might be essential for completing the subtask, but Person A might be so difficult to work with that only a few members of the larger group can work with Person A in harmony

Communications technology reduces location constraints on subgroups

If the task demands that subgroup members work closely together and communicate often, then even as recently as 1990 or 2000, we would almost always assign people to the subgroup so that everyone was at the same site, or working in the same city or building. In terms of priority for assignment to subtask, someone's location might have rivaled their skill set.

Today's communications technologies can greatly diminish the impact of the location constraint. Access to videoconference technology is now so widespread that geography provides a much-reduced constraint on subgrouping. The demands of the task and personnel availability are now much more dominant than they once were.

Conway's Law

Conway's Law (the Law) Access to videoconference technology

is now so widespread that geography

now provides only a much-reduced

constraint on subgroupingisn't actually a law in the legal sense. It's a pattern first described in 1968 by computer scientist Melvin Conway, and named "Conway's Law" by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month. [Conway 1968] [Brooks 1982] The Law says, "…organizations which design systems…are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." Conway also observes:

This kind of a structure-preserving relationship between two sets of things is called a homomorphism. Speaking as a mathematician might, we would say that there is a homomorphism from the linear graph of a system to the linear graph of its design organization.

As Conway puts it even more concisely, "Systems image their design groups." Specifically, for each pair of interacting system elements A and B, there is an interacting pair of groups of system designers, A' and B', respectively responsible for system elements A and B.

Conway's Law has implications that reach beyond system design. For example, it's likely a cause of the formation or persistence of technical debt in cases where reorganizations or organizational acquisitions have broken the homomorphism between the social architecture of the organization and the technical architectures of the systems that organization maintains. [Brenner 2019.4] [Brenner 2019.5]

The role of Conway's Law in subgrouping

Subgrouping might also provide an example of Conway's Law. But in a fascinating twist, in subgrouping, the Law can have influence in a direction opposite to the sense of the law as expressed by Conway. One can understand how the Law constrains an organization to produce system designs that, in Conway's words, "image their design groups." But suppose a task-oriented work group is performing maintenance on an existing system. When that work group forms subgroups, the demands of the task constrain how the subgroups form. In this way, the subgroups image the system.

If this is so, then when the task requires a period of intensive work on Subtask A, the work group would tend to form a subgroup (Subgroup A) to attend to Subtask A. Subgroup A might then develop along the lines of Tuckman/Jensen's Developmental Sequence for small groups, finally Adjourning when Subtask A is complete. [Tuckman & Jensen 1977]

Communications technology weakens the geographical constraint

Formerly, the geolocation of group members constrained communication patterns. That is, people who needed to work closely together had to be located conveniently to each other. Now, though, as noted above, geography plays a more limited role in determining communication convenience.

Consequently, when subgroups form, geography likewise plays a more limited role than it did even 20 years ago. By employing modern communications technologies, we gain freedom to define subgroups that more closely produce a homomorphism between the work underway and the subgroup structure.

Last words

Meanwhile, while Subgroup A does its work, other subgroups might "form, develop, and adjourn in parallel with Subgroup A, though not necessarily in synchrony. In very large groups, a subgroup "foam" might develop, with each subgroup progressing through its own Tuckman/Jensen stages at its own rate. Potentially, at any given time, one subgroup or another might always be Storming. To an outside observer, the larger group might appear to be constantly Storming, and so chaotic as to provide a counterexample to Tuckman's model of group development, when actually Tuckman's model is being confirmed many times over, subgroup-by-subgroup. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Nine Positive Indicators of Negative Progress

Nine Positive Indicators of Negative Progress- Project status reports rarely acknowledge negative progress until after it becomes undeniable. But projects

do sometimes move backwards, outside of our awareness. What are the warning signs that negative progress

might be underway?

Nine Project Management Fallacies: II

Nine Project Management Fallacies: II- Some of what we "know" about managing projects just isn't so. Identifying the fallacies of

project management reduces risk and enhances your ability to complete projects successfully.

Nonlinear Work: Internal Interactions

Nonlinear Work: Internal Interactions- In this part of our exploration of nonlinear work, we consider the effects of interactions between the

internal elements of an effort, as distinguished from the effects of external changes. Many of the surprises

we encounter in projects arise from internals.

The Retrospective Funding Problem

The Retrospective Funding Problem- If your organization regularly conducts project retrospectives, you're among the very fortunate. Many

organizations don't. But even among those that do, retrospectives are often underfunded, conducted by

amateurs, or too short. Often, key people "couldn't make it." We can do better than this.

What's stopping us?

Anticipating Absence: Why

Anticipating Absence: Why- Knowledge workers are scientists, engineers, physicians, attorneys, and any other professionals who

"think for a living." When they suddenly become unavailable because of the Coronavirus Pandemic,

substituting someone else to carry on for them can be problematic, because skills and experience are

not enough.

See also Project Management and Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!