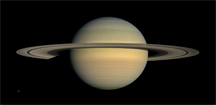

Saturn during equinox — a composite of natural-color images from Cassini. Except for extremely rare events, planetary bodies move on a predictable schedule.

NASA image courtesy Wikipedia.

The first prerequisite for rescheduling any effort — the absolute must-have without which rescheduling is totally impossible — is a schedule. If you don't have a schedule you can't modify it. You're not in much better shape if your schedule is delusional, by which I mean that the schedule you do have is an over-optimistic fiction that nobody ever believed, or an out-of-date artifact the origin of which nobody still working here can remember. Rescheduling a delusional schedule is itself a delusion, because you didn't really have a schedule. But let's face it, when you're rescheduling a delusional schedule, you're probably just making another delusional schedule.

But I digress.

In any group of people engaged in collaboration, natural questions arise. For example, "When do you think you'll have X ready?" When someone asks a question like that, devising a schedule is probably going to happen. In some groups more formally managed, devising a schedule is one of the early tasks. If the group is large enough, or if the work is complicated enough, or if people outside the group are depending on the group to produce something real, the group will almost certainly need to devise a schedule. And just as certainly, in the fullness of time, they'll find it necessary to revise that schedule. So whenever you find yourself devising a schedule, set aside time in that schedule for revising the schedule. The one thing you can be certain of about any schedule is that you'll need to revise it.

To answer the need for expertise in rescheduling, this post and several to come explore the process of rescheduling. I'll address four fundamental questions about rescheduling:

- What is a schedule?

- What situations compel collaborative groups to reschedule their work?

- What patterns indicate effective rescheduling processes?

- What antipatterns indicate ineffective rescheduling processes?

In this post I address only the first question. I address the others in posts to come.

What a schedule is

Before undertaking to reschedule any effort, it's useful to know what we mean by schedule. In the context of executing an effort to produce a desired result, a schedule is a sequence of events or activities and their associated date specifications. Some definitions:

- Event

- An event is the production of an intended and observable result. An example of an observable result: "The Customer has witnessed a demonstration of our widget and has agreed that it does what the Customer wanted our widget to do."

- Too often, Whenever you find yourself devising a schedule,

set aside time in that schedule to reschedule the

effort. The one thing you can be most certain of

about any schedule is that you'll need to revise it.schedules contain pseudo-events. A pseudo-event is a date or date range not associated with production of an intended, observable result. For example, "We have exerted 50% of the total effort that we estimated would be required by this work." While it might have been intended, consuming 50% of estimated effort is not an observable result. - The event date can be specified as either a specific date, or a range of dates from earliest acceptable to latest acceptable. If the event has a single date associated with it, it's usually permissible for the result to occur earlier. If the event has an associated date range, the two dates at the ends of the range are usually "earliest-acceptable" and either "latest acceptable" or "needed-by."

- Activity

- An activity is an intended, observable, ongoing action or set of actions that continues during the specified range of dates, until its exit criteria are met. An example of an activity: "The team meets with Customer to develop a complete set of acceptance criteria that relate to validating the Marigold installation." The exit criterion for such a task might be "Team and Customer agree."

- Too often, schedules contain pseudo-activities. A pseudo-activity is similar to an activity but it lacks one or more of the attributes of an activity. It might lack dates, or exit criteria, or it might not be observable. For example, a pseudo-activity might be "In the first week of March, team members attend one week of training in writing user stories." Although this pseudo-activity has dates and although it is observable, it lacks exit criteria. We have no evidence that Team members learned anything.

The first step in rescheduling

A useful first step in rescheduling — often overlooked — is verifying that the existing schedule is actually a schedule. There are three basic criteria:

- All events are observable. They have dates or date ranges.

- All activities are observable. They have exit criteria and date ranges.

- Dates occur in transitive time order, even though they might be in the past. That is, if Event 3 is supposed to occur after Event 2, and Event 2 is supposed to occur after Event 1, then Event 3 is scheduled to occur after Event 1.

Last words

After checking the existing schedule to ensure that it meets the three criteria above, you're ready to set new dates for events and activities that aren't yet completed. I'll address that part of the process in posts to come. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Team Thrills

Team Thrills- Occasionally we have the experience of belonging to a great team. Thrilling as it is, the experience

is rare. How can we make it happen more often?

Shining Some Light on "Going Dark"

Shining Some Light on "Going Dark"- If you're a project manager, and a team member "goes dark" — disappears or refuses to

report how things are going — project risks escalate dramatically. Getting current status becomes

a top priority problem. What can you do?

Project Improvisation and Risk Management

Project Improvisation and Risk Management- When reality trips up our project plans, we improvise or we replan. When we do, we create new risks

and render our old risk plans obsolete. Here are some suggestions for managing risks when we improvise.

Why Scope Expands: I

Why Scope Expands: I- Scope creep is depressingly familiar. Its anti-partner, spontaneous and stealthy scope contraction,

has no accepted name, and is rarely seen. Why?

The Ultimate Attribution Error at Work

The Ultimate Attribution Error at Work- When we attribute the behavior of members of groups to some cause, either personal or situational, we

tend to make systematic errors. Those errors can be expensive and avoidable.

See also Project Management and Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!