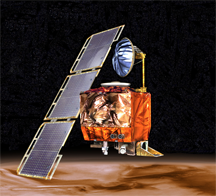

NASA's Mars Climate Orbiter, which was lost on attempted entry into Mars orbit on September 23, 1999. It either crashed onto the surface of Mars or escaped Mars gravity and entered a solar orbit. The failure was due to mismatch of measurement units in two software systems. A NASA-built system used metric units and a system built by Lockheed Martin used "English" units. If the two teams had conducted more open discussions, the loss of the orbiter might have been averted. NASA artist's rendering courtesy Wikimedia.

Would anyone object? It's an innocent question that might be posed by a team member who's acting in a role that serves the rest of the team in some way. Example: "Would anyone object if we move the Backlog Review Meeting to 1100 on Thursdays?" Perhaps the role in question is Secretary, or Host Site rep, or Scribe, or meeting planner, or ScrumMaster, or project manager, or speaker committee chair. To people in these roles, asking for objections before making a decision seems like a convenient way to ensure acceptable levels of decision quality in a timely fashion. It avoids convening a meeting, with all the hassle and delay that accompanies meetings.

Convenient and quick it may be, but there are risks. Many of those risks trace to one root cause: constraining the time spent in open discussion.

The risks of asking only for objections

To exhibit these risks clearly, one need only compare the would-anyone-object process, conducted through chats or email, to the lets-discuss-it-in-a-meeting process. In what follows, I refer to the team member who posed the question as Quentin (Q for Question). And I assume that the meeting would be a meeting or videoconference of the individuals Quentin queried, in which the attendees conduct an open discussion.

- Risk of abusing delegated authority

- In an open discussion in a meeting, all attendees can see each other and hear each other's responses to Quentin's question. When Quentin poses the question in a chat or email, the people queried might not have access to each other's responses. If some people respond only to Quentin, he's free to count their responses as he chooses. That would be an outrageous abuse of authority, of course, but it could happen. More likely, but still problematic, are errors Quentin might make in processing the responses.

- Risk of overlooking important factors

- When Asking for objections before making a

decision might seem like a convenient

way to ensure acceptable levels of

decision quality, but it comes

with some significant risksQuentin asks for objections only, respondents might not provide other pertinent information that could affect the decision. For example, suppose Kelly knows that an audit that has been underway will finish on Thursday, making unnecessary consideration of the matter at hand. Kelly might not mention this, because it isn't an objection. In a meeting, on the other hand, an open discussion might be more likely to surface such information. - Risk of working with misinformation

- Similar to the risk of overlooking important factors is the risk of working with misinformation — information that's outdated, incomplete, or just plain wrong. In an open discussion in a meeting, intentional efforts to vet all assumptions and contributions can mitigate this risk. For example, someone might object on the basis of outdated information. In a meeting, other attendees can question the basis of the objection, and that can reveal the error. Asking for objections in a chat or email is much less likely to provide such mitigation.

- Risk of overlooking important constituents

- If all individuals affected by the decision are included in the group from whom Quentin seeks objections, then the risk of overlooking constituents might be no greater for Quentin's approach than it would be for a meeting. But if there are many other affected individuals, Quentin's approach has a high risk of missing the objections of people not included in his query. And this point would likely surface (read: "should be surfaced") in a meeting.

- Risk of communication gaps

- When we rely on asking for objections in a chat or email, communication gaps can appear in a variety of forms:

- Intended recipients might not receive Quentin's query

- The query might have been sent to people who should not have been queried

- The recipient might misunderstand the query

- The recipient might choose not to respond

- The recipient might forget to respond

- Quentin might not receive the recipient's response

- Quentin might not understand the recipient's response

- …and many more

- A face-to-face meeting is likely to experience these difficulties at a much lower rate. Even if they do occur in a meeting, they're more evident to everyone and more easily resolved. The same is true, to a lesser extent, for virtual meetings.

Last words

If you've read to this point, you might have noticed an unstated assumption underlying this risk catalog. That unstated assumption is that Quentin earnestly wants to know whether or not there are objections. He wants to ensure that the decision he makes is a good one. But there are other much less benign possibilities.

Quentin might want to suppress open discussion. The would-anyone-object process actually suppresses discussion, which reduces the probability of new information coming to light. Reducing the probability of discovering issues enhances the probability that the decision process will produce the outcome Quentin is proposing. Anyone intent on producing the outcome they favor would thus find the would-anyone-object process appealing. It's an effective tool for controlling group decision-making, and when used for that purpose, it's ethically questionable. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Do you spend your days scurrying from meeting to meeting? Do you ever wonder if all these meetings are really necessary? (They aren't) Or whether there isn't some better way to get this work done? (There is) Read 101 Tips for Effective Meetings to learn how to make meetings much more productive and less stressful — and a lot more rare. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Meetings:

Twelve Tips for More Masterful Virtual Presentations: II

Twelve Tips for More Masterful Virtual Presentations: II- Virtual presentations are unlike face-to-face presentations, because in the virtual environment, we're

competing for audience attention against unanticipated distractions. Here's Part II of a collection

of tips for masterful virtual presentations.

Chronic Peer Interrupters: II

Chronic Peer Interrupters: II- People use a variety of tactics when they're interrupted while making contributions in meetings. Some

tactics work well, while others carry risks of their own. Here's Part II of a little survey of those tactics.

Chronic Peer Interrupters: III

Chronic Peer Interrupters: III- People who habitually interrupt others in meetings must be fairly common, because I'm often asked about

what to do about them. And you can find lots of tips on the Web, too. Some tips work well, some generally

don't. Here are my thoughts about four more.

Brainstorming and Speedstorming: II

Brainstorming and Speedstorming: II- Recent research into the effectiveness of brainstorming has raised some questions. Motivated to examine

alternatives, I ran into speedstorming. Here's Part II of an exploration of the properties

of speedstorming.

Barriers to Accepting Truth: I

Barriers to Accepting Truth: I- In workplace debates, a widely used strategy involves informing the group of facts or truths of which

some participants seem to be unaware. Often, this strategy is ineffective for reasons unrelated to the

credibility of the person offering the information. Why does this happen?

See also Effective Meetings and Effective Meetings for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!