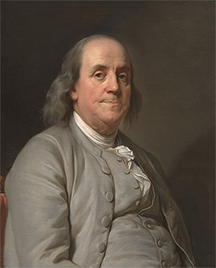

Benjamin Franklin portrait by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, ca. 1785. (It is this image that appears on the U.S 100-dollar bill) Benjamin Franklin participated in the Constitutional Convention that led to the creation of the United States of America. His role was that of sage elder, lending weight to the body — what I call "clout" here — that was sorely needed. He made several critical suggestions at key points in the development of the constitution.

Sometimes those who possess clout use it well. Sometimes we are wise to heed them.

Photo of a painting of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Siffred Duplessis held at the U.S National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution.

From time to time, we become so involved in debating with each other that we can forget that for most issues we debate at work, Reality has the final say. It happens like this. We encounter a situation that has no obvious or immediate resolution. We debate the issue for a time, and finally settle on a path that nobody is really comfortable with. Then we push ahead, hoping that somehow it will all work out.

But Reality — not any debater's skill or stature — ultimately decides every question. Here's an example:In scenarios like this, people don't seem concerned that Reality hasn't had a chance to contribute to the debate. Nobody has suggested a "pilot," and the Pragmatists failed to sway the Visionaries by citing the difficulties previous efforts have had. And so, Reality is set aside until Franklin's Compromise Approach is either successful — or not. It's white-knuckle time.We go back and forth on this question, until someone who's highly respected — someone with "clout" whom I'll call Franklin — proposes a Compromise Approach. The Visionaries and Pragmatists agree to hire a few more people and acquire more powerful software. But although these measures were among those the Pragmatists wanted, much of what they wanted is excluded.

Clouted thinking

What The person who has the clout isn't necessarilyengaged in nefarious activity. It's often the

person with clout who is thinking most cloutedly.has happened in scenarios like the one above might be regarded as analogous to the consequences of a cognitive bias known as the halo effect. [Thorndike 1920] The halo effect is our tendency to allow positive (negative) impressions of one attribute of a person, company, country, brand, product, or any entity, really, to positively (negatively) influence our assessment of other attributes of that same person, company, country, brand, product, or entity. In the scenario above, both Visionaries and Pragmatists accept Franklin's Compromise Approach. It might be a good solution. But it's also possible that the halo effect has taken over. It's possible that their willingness to adopt Franklin's compromise was influenced, in part, by Franklin's stature — by his clout. Their thinking might have been something like, "Franklin knows his stuff, so maybe his idea will actually work." And that's the problem. Franklin knows his stuff. He has a record of accomplishment in some specific domains in which he earned his clout. But is that record applicable to the matter at hand? Perhaps. In many cases it is applicable. But too often, the halo effect causes us to accept the suggestions of the Franklins of the world even when the domains in which they earned their clout aren't relevant to the matter at hand. I call this pattern clouted thinking. The person who has the clout isn't necessarily engaged in nefarious activity. It's often the person with clout who is thinking most cloutedly.

Indicators of clouted thinking

Clouted thinking is one of the harmful effects of clout. Detecting clouted thinking can be difficult. But one aid in avoiding trouble is sensitivity to the kinds of comments people make when they're engaging in clouted thinking. Here are five indicators that the risk of clouted thinking is elevated.- Discarding some evidence while crediting other evidence

- Knowing what to attend to and what to set aside is essential for resolving complex problems. Be alert to the arbitrary application of the technique. Inconsistency in what we accept or reject can be driven by a desire to reach a specific outcome.

- I prefer my opinion to yours

- Preference for one opinion over others is not evidence of the validity of that opinion. Preference for an opinion is not a reason to be guided by that opinion. Demand evidence.

- If you can't explain why it's happening, it isn't happening

- It's irrational to reject an observation of system behavior as invalid on the basis that no known model of the system can account for that behavior. Instead, when our models cannot account for system behavior, we must accept that our models of the system are incomplete or incorrect. Models can be wrong. Reality is always right.

- It can't (must) be true because people with clout say so

- Accepting as facts the assertions of people with clout is one way of detaching the debate from Reality. The pronouncements of people with clout then become facts for purposes of the debate. And unlike actual facts, pronouncements can be mistaken or fabricated. Demand Reality-based evidence.

- You're wrong, because you're contradicting someone with clout

- People with clout are typically correct more often than others, but they do make mistakes, too. And people who lack clout can occasionally report correct observations, or occasionally have good ideas. It's irrational to reject (or accept) a statement on the sole basis of its author's stature. Demand evidence.

Last words

The suggestions above mention the need for evidence repeatedly, but they don't define the term. Evidence is fact. Statements by reliable individuals are sometimes the closest we come to gathering facts. Statements, when taken as fact, can sometime lead us to clouted thinking. Handle statements with care.

Do you spend your days scurrying from meeting to meeting? Do you ever wonder if all these meetings are really necessary? (They aren't) Or whether there isn't some better way to get this work done? (There is) Read 101 Tips for Effective Meetings to learn how to make meetings much more productive and less stressful — and a lot more rare. Order Now!

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Cognitive Biases at Work:

The Stupidity Attribution Error

The Stupidity Attribution Error- In workplace debates, we sometimes conclude erroneously that only stupidity can explain why our debate

partners fail to grasp the elegance or importance of our arguments. There are many other possibilities.

On Standing Aside

On Standing Aside- Occasionally we're asked to participate in deliberations about issues relating to our work responsibilities.

Usually we respond in good faith. And sometimes we — or those around us — can't be certain

that we're responding in good faith. In those situations, we must stand aside.

Motivated Reasoning and the Pseudocertainty Effect

Motivated Reasoning and the Pseudocertainty Effect- When we have a preconceived notion of what conclusion a decision process should produce, we sometimes

engage in "motivated reasoning" to ensure that we get the result we want. That's risky enough

as it is. But when we do this in relation to a chain of decisions in the context of uncertainty, trouble

looms.

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II- Plans are well known for working out differently from what we intended. Sometimes, the unintended outcome

is due to external factors over which the planning team has little control. Two examples are priming

effects and widely held but inapplicable beliefs.

Mental Accounting and Technical Debt

Mental Accounting and Technical Debt- In many organizations, technical debt has resisted efforts to control it. We've made important technical

advances, but full control might require applying some results of the behavioral economics community,

including a concept they call mental accounting.

See also Cognitive Biases at Work and Cognitive Biases at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!