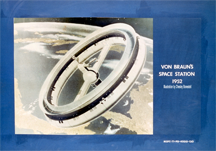

A model of a space station proposed in 1952 by Wernher von Braun as a way station for manned Mars exploration. He proposed a scaled-down version in 1955 to play a similar role for manned Moon exploration. That station is featured in a YouTube video produced in collaboration with Disney studios. Illustration by Chesley Bonestell. Image courtesy NASA via Wikimedia.

Developing new products or new services often begins with recognizing the existence of a problem not previously noticed. Because new opportunities are rare, speed in bringing that new product or service to market is a critical element of success. And that requires that we find a solution to the problem as quickly as we can. We try to do so, but efforts to manage financial risk frequently lead to underfunding the problem definition phase, which causes delays and lengthens time-to-market.

People in modern organizations generally regard project teams as being the points where most of the work of problem solving occurs. When we consider ways of achieving ever higher-velocity problem solving, we tend to assume that the greater portion of velocity improvement lies in helping project teams solve their problems faster. But that point in the problem-solving life cycle might not be the place where improvements are most needed. Improving problem definition might yield even greater gains in velocity.

Why problem definition is so important

In the context of solving problems, velocity is only conceptual, because we cannot actually measure problem-solving velocity. What we can measure is the time interval between conceiving an objective and achieving it. But for solving problems, that measurement is still a bit squishy. Solving a difficult, complex problem often entails adjusting the problem definition using the knowledge we gain from our initial problem-solving attempts. The goal we finally achieve is often different from the goal we set out to achieve, because we re-define the goal based on what we learn from early attempts to reach it.

That's why higher-velocity problem definition can be critical to success.

Consider, for example, the problem of sending people to the Moon and back. One approach was clear by the early 1950s, as illustrated in a YouTube video narrated by Wernher von Braun. This early solution involved a rotating wheel-shaped space station with a crew of 50. Among other missions, the station was to act as a fuel depot for the lunar expedition vehicle, which was to carry a crew of 10. Compare this to the solution ultimately adopted by NASA, which had no space station. It had a lunar expedition vehicle with a crew of only three. NASA's approach had so little in common with the early solution that one might reasonably conclude that the two solutions were addressing two different problems. Between the early 1950s and the early 1960s the problem definition had sharpened. And that sharpening — that refining of the problem definition — is a pattern common to the solution histories of many complex problems.

Improving problem definition might yield gains in velocity even greater than improving problem solving. Those gains become available only if we're willing to invest consciously and directly in problem definition efforts. But we're rarely willing to invest at the needed levels because of what might be called the problem definition paradox.

The problem definition paradox

A fundamental We continue to try to solve

complex problems before

we've adequately refined

the problem definitionpractice of high-velocity problem solving is higher-velocity problem definition. And that's where the trouble now lies. We can solve complex problems more rapidly if we can find ways to accelerate the problem definition process. But we continue to try to solve complex problems before we've adequately refined the problem definition. This difficulty can be understood as a consequence of our paradoxical approach to funding the problem definition process.

In conventional new product development, the problem definition process establishes the goal. It defines in broad strokes what the new product (or service) will provide. When we feel that the definition has been sufficiently refined, only then do we apply resources to developing the new product or service in question.

But difficulties can arise, because we cannot truly understand complex problems until we try to solve them, or at least, until we try to solve less complex versions of them. These early attempts to solve problems, even in their early forms, are costly. And so we withhold serious investment until such time as we have a problem definition that meets our thresholds for stability and clarity.

Typically, we develop these problem definitions over months and sometimes years of endless meetings, repetitive debates, occasional prototypes, and much use of PowerPoint. Finally, we invest a little in a demonstration effort that we call a "proof of concept." If the investment in the demonstration is large enough, the sunk cost effect ensures that the concept will be declared proven, whatever the outcome of the proof-of-concept effort.

But therein lies the paradox. On a shoestring budget we cannot develop a problem definition that's sharp enough, focused enough, complete enough, and stable enough to support commitment of resources sufficient for success. Consequently, when we apply those resources to the problem solution effort, a significant fraction must be dedicated to problem redefinition. We end up spending the resources we thought we had saved. But they're spent instead on development dead ends that could have been avoided by investing more heavily in problem definition. And by limiting expenditures on problem definition, we pay the additional penalty of schedule slippage.

The paradox is that avoiding serious investment until we have what we think is an adequate problem definition prevents us from developing a truly adequate problem definition. This happens because for complex problems, developing an adequate problem definition requires serious investment.

Untangling the paradox

Here are four strategies for achieving higher-velocity problem definition.

- Regard problem definition refinement as investment

- Refining a problem definition is an investment. The return on that investment is more rapid development of the ultimate solution to the problem. And that can lead to shorter time-to-market overall.

- Avoiding investment in early problem definition refinement can lead to false starts when product development begins. The cost of those false starts can exceed by far any amounts saved by reducing investment in problem definition refinement.

- Replace the term "proof of concept"

- The term "proof of concept" — and its shorter cousin "POC" — biases those tasked with investigating the validity of the concept. The bias arises because the term suggests that the mission of the investigation task is providing proof that the concept is valid, rather than assessing the validity of the concept. Because the effort is biased, the team engaged in the work is at risk of finding that the concept is valid when it is not.

- What's actually needed is an objective assessment of the concept's ability to contribute to achieving the goal. Devise a term that more accurately describes the mission. Words like "investigation," "experiment," or "assessment" are more appropriate than "proof."

- Start investigating the problem before you're "ready"

- In many organizational cultures, the current definition of "readiness" for solving a problem sets too high a threshold for committing resources at levels needed for problem definition refinement.

- Unless you feel that the resource requests for problem definition refinement are premature or excessive given the current state of knowledge, you're probably thinking about committing those needed resources later than they're actually needed.

- Field multiple independent problem definition efforts

- Simultaneous independent problem definition efforts provide two valuable advantages. First, their independence enhances the probability of discovering important attributes of the problem. Second, because they proceed in parallel, their results are available more rapidly than a single effort could produce.

- With multiple parallel independent efforts underway, a spirit of competition could develop, which would also benefit the organization by motivating the competitors to address the problem creatively.

Finally, be willing to discard first efforts, even after they've entered service. A willingness to discard them is a way of mitigating the risk that problem solving was declared complete while problem definition was still underway. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Bonuses

Bonuses- How we deal with adversity can make the difference between happiness and something else. And how we

deal with adversity depends on how we see it.

Forward Backtracking

Forward Backtracking- The nastiest part about solving complex problems isn't their complexity. It's the feeling of being overwhelmed

when we realize we haven't a clue about how to get from where we are to where we need to be. Here's

one way to get a clue.

Reactance and Decision Making

Reactance and Decision Making- Some decisions are easy. Some are difficult. Some decisions that we think will be easy turn out to be

very, very difficult. What makes decisions difficult?

Tackling Hard Problems: I

Tackling Hard Problems: I- Hard problems need not be big problems. Even when they're small, they can halt progress on any project.

Here's Part I of an approach to working on hard problems by breaking them down into smaller steps.

Thirty Useful Questions

Thirty Useful Questions- Whether solving technical problems, creating plans, or puzzling through political tangles, asking the

right questions can be the key to finding useful approaches. An example: What questions would I like

to know the answers to?

See also Problem Solving and Creativity and Problem Solving and Creativity for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!