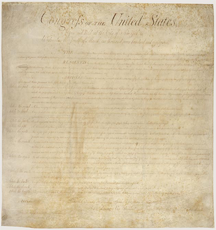

The Bill of Rights — the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The Bill actually was a Bill, introduced in the First Congress, and sent on after much wrangling, to the states for ratification. How it came about is a wonderful illustration of the approach to impasse that is founded on acceptance and serious consideration of the views of dissenters. Ratification of the Constitution was a controversial decision, with two views contending for dominance. The dominant group were the Federalists, who favored a strong central government and who felt that no enumeration of rights was advisable. The dissenting minority were the Anti-Federalists, who were wary of strong central government and who wanted specific protection of individual rights. Ratification of the Constitution met serious opposition in some states, including in Massachusetts. But it succeeded there based on an approach that came to be known as the Massachusetts Compromise, which enabled Anti-Federalists to vote to ratify the Constitution in exchange for a commitment by Federalists to consider the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights. This compromise was replicated in other states where ratification was problematic, and on September 13, 1788, the Constitution was finally declared ratified, albeit at that time by only 11 of the thirteen states that eventually ratified it.

The first Congress met in New York City on March 4, 1789, dominated by the Federalists, 20 to 2 in the Senate, and 48 to 11 in the House. It was this First Congress that adopted and sent to the states for ratification the Bill of Rights, which dealt specifically with the Anti-Federalists' objections. Read more about the history of the Bill of Rights. Photo courtesy .

We began an exploration of impasses last time by focusing on the perspective of opinion minorities. In our scenario, we postulated that the group did have consensus on some issues, which we called the C-Issues. But there was disagreement on other issues — the D-Issues. In this Part II, we explore two tactics that tend to strengthen the impasse, preventing agreement.

- Hostage tactics

- Some group members believe that by taking hostages, they can compel the rest of the group to adopt a position more to their liking. The hostage of choice is often one or more of the C-Issues. In the view of the hostage takers, refusing to agree to the C-Issues exerts pressure on the rest of the group to comply with the hostage-takers' wishes. This tactic can become corrosive if members of the rest of the group press the hostage-takers to justify their opposition to the hostage C-Issues. The hostage-takers then devise arguments to justify their opposition to the C-Issues, which, often, they themselves don't believe. What little agreement there was with respect to C-Issues might then vanish. Even worse, others in the group might become intransigent, if they feel that acceding to the hostage-takers' demands will only invite further demands and further hostages, either by the hostage-takers or by others who witness the success of the hostage-takers.

- Acceding to hostage-takers' demands might seem appealing, but it does usually lead to more widespread hostage taking. Because questioning the hostage-takers about C-Issues risks converting C-Issues to D-Issues, approaches to forging agreement must always focus on D-Issues. Make the concerns of the objectors visible, and deal with them substantively.

- Abuse of the concept of precedent

- Some group members might fear that after they agree to the C-Issues, they won't be able to influence subsequent decisions sufficiently with respect to the D-Issues. They see partial agreement as the first step on a slippery slope, fearing that others will use their partial agreement as inappropriate leverage for later decisions. In effect, they fear they might be confronted with, "I don't see what your problem is with D-Issue #3, because you agreed to C-Issue #2." That tactic can indeed be an abuse of the concept of precedent, if it relies solely on the fact of agreeing to C-Issue #2, rather than on the substance of C-Issue #2, the substance of D-Issue #3, and their connection.

- If abuse of precedent Acceding to hostage-takers' demands

might seem appealing, but it does

usually lead to more

widespread hostage-takinghas occurred in the past, then certainly the concern is real, and the group must deal with it. To address the concern, the group can agree that such content-free appeals to precedents are unacceptable.

Hostage-taking by dissenters, or precedent abuse by those pressuring dissenters, are indirect attempts to gain adherents. To avoid strengthening impasses, deal directly with objections to agreement. First in this series Next in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

Confronting the Workplace Bully: II

Confronting the Workplace Bully: II- When bullied, one option is to fight back, but many don't, because they fear the consequences. Confrontation

is a better choice than many believe — if you know what you're doing.

Preventing Spontaneous Collapse of Agreements

Preventing Spontaneous Collapse of Agreements- Agreements between people at work are often the basis of resolving conflict or political differences.

Sometimes agreements collapse spontaneously. When they do, the consequences can be costly. An understanding

of the mechanisms of spontaneous collapse of agreements can help us craft more stable agreements.

So You Want the Bullying to End: I

So You Want the Bullying to End: I- If you're the target of a workplace bully, you probably want the bullying to end. If you've ever been

the target of a workplace bully, you probably remember wanting it to end. But how it ends can be more

important than whether or when it ends.

Bullying by Proxy: I

Bullying by Proxy: I- The form of workplace bullying perhaps most often observed involves a bully and a target. Other forms

are less obvious. One of these, bullying by proxy, is especially difficult to control, because it so

easily evades most anti-bullying policies.

Toxic Disrupters: Responses

Toxic Disrupters: Responses- Some people tend to disrupt meetings. Their motives vary, but their techniques are predictable. If we've

identified someone as using these techniques we have available a set of effective actions that can guide

him or her toward a more productive role.

See also Conflict Management and Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!