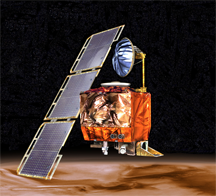

NASA's Mars Climate Orbiter, which was lost on attempted entry into Mars orbit on Sptember 23, 1999. It either crashed onto the surface of Mars or escaped Mars gravity and entered a solar orbit. The failure was due to mismatch of measurement units in two software systems. A NASA-built system used metric units and a system built by Lockheed Martin used "English" units. NASA artist's rendering courtesy Wikimedia.

All organizations eventually make mistakes. And if conditions are right, the people of the organization can learn from their mistakes. One of the conditions that makes learning from mistakes possible is that the mistake must not be fatal to the organization. When the organization survives the mistake, its people might have opportunities to avoid repeating the mistake. For this post, then, the mistakes of interest are those that could be repeated.

Some mistakes are so consequential that the word mistake is inadequate. For the cases of interest here — mistakes that aren't lethal for the organization — calamity and catastrophe are too strong, because they include the possibility that the organization itself might be destroyed as a consequence of having made the mistake, which would make those mistakes unrepeatable. The kind of mistake I have in mind has very severe consequences, but not so severe that the organization comes to an end. That kind of mistake lies somewhere between Volkswagen diesel emission testing and Enron accounting practices. In this post, I'll use the word blunder to denote the kind of grave-but-not-fatal errors I have in mind.

If you work in an organization, how the organization handles blunders can affect your livelihood and even your career. You depend on the organization and its people not to repeat repeatable blunders. When blunders happen, you depend on the organization and its people to behave ethically and to deal with the blunders effectively. It is therefore in your interest to know how to recognize factors that cause organizations to tend to repeat repeatable blunders. When you notice these factors, you can take action to address them, or you can decide to move on.

In this post I offer an If you work in an organization,

how the organization handles

blunders can affect your

livelihood — and your careerelementary survey of the options organizations and their people have when blunders happen. Knowing the range of options is helpful when you're assessing your relative safety as a member of an organization. When a blunder occurs, the organization and its people can choose among acknowledgment, concealment, and denial.

- Acknowledgment

- If the organization and its people acknowledge the blunder, they can determine how and why it happened. They can then use that information to make adjustments and prevent repetitions. Even so, if they acknowledge the blunder, they risk public exposure, which can cause damage to the organization's image.

- Acknowledgment is the one choice that can lead to a benign or even favorable outcome. However, the short-term damage to the organization's image, and the voluntary turnover that can comprise some of the damage, can be costly indeed, to the organization and to its people, especially those involved in the incident.

- Concealment

- If the organization and its people conceal the blunder, they can reduce the probability of public exposure, which can limit damage to the organization's image. But concealing the blunder risks hampering the investigation of the blunder's causes. That, in turn, can delay or inhibit developing preventions, which makes the blunder more repeatable. Even if the search for causes and preventions does proceed, concealing the blunder risks biasing the conclusions of the investigation.

- Unless the blunder and its consequences are highly localized, and knowledge of it is limited to a small circle of individuals, concealment is likely to be effective only in the short term. Eventually, evidence of the blunder will become public. When that happens, evidence of the concealment might also become public. The concealment might even become more damaging to the organization's image than was the original blunder.

- Denial

- If the organization and its people deny the blunder, even to themselves, they cannot investigate it. There is therefore no opportunity to find causes or preventions. Moreover, denial makes effective concealment more difficult, because concealing the blunder requires enough awareness of it to enable manufacturing alternative explanations for any evidence that might somehow emerge.

- We can regard denial as an extreme form of concealment, in which the organization and its people conceal the blunder even from themselves. But because denial limits the ability to conceal the blunder, denial is even more likely to lead to exposure than ordinary concealment. As a strategy, denial is therefore less effective than concealment.

Concealment and denial tactics

Some organizations routinely conceal blunders, including both high-level organizational blunders, and blunders by individuals within the organization. Usually, participants in the concealment effort mean well in the sense that the motivation is protecting the reputation of the organization or the individual.

But high-minded intentions don't relieve the organization of its ethical and legal obligations. When concealment and denial become the dominant response strategies, your own professional integrity can be at risk. Familiarity with the variety of tactics used to conceal or deny blunders is therefore helpful in evaluating the risks associated with remaining in an organization that conceals or denies its blunders. Here's a short catalog of some of these tactics.

- Transferring witnesses or potential witnesses to different locations, or terminating their employment

- Offering incentives to people for cooperating with a concealment or denial strategy

- Extensive use of comprehensive nondisclosure agreements, either upon termination or as a condition of employment or continued employment

- Destroying evidence by shredding documents or shredding digital data storage equipment

- Disseminating false or misleading information to the public or to employees

- Discrediting, sometimes prospectively, individuals who have access to information related to the blunder

- Scapegoating, especially by termination

- Threatening uncooperative individuals or media organizations

- Confessing to something less damaging

If you notice any of these tactics in use, but they haven't yet been directed at you or involved you, you might feel safe. But feelings of safety can be fleeting. Events can become complicated quickly.

Last words

Concealment or denial strategies are appealing because they seem to offer a means of limiting the blunder's damage. These strategies can indeed limit the cost of direct consequences of the blunder. But the costs of concealment or denial strategies can be unexpectedly high when we consider indirect consequences.

As an example of indirect consequences, suppose there is a bully at large in the organization. Suppose this bully has already wrecked two or three careers. Helping the current target of the bully by intervening with disciplinary action against the bully could expose the organization to liability actions brought by past targets. That liability constitutes indirect consequences of intervening in the bully's activities.

To prevent those indirect consequences, organizations sometimes avoid confronting their bullies or intervening on behalf of bullies' targets. But these strategies leave the bully in place, free to harm more careers. Some people leave the organization. Output suffers. Work is delayed. Because the costs of these indirect consequences of intervening to prevent further bullying are difficult to measure with precision, few organizations try to do so. Concealment and denial thus become the strategies of choice.

Concealment and denial strategies are most appealing for people under stress. Detecting them can be difficult, especially for people who want to believe they aren't happening. Watch carefully. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Devious Political Tactics:

Some Hazards of Skip-Level Interviews: III

Some Hazards of Skip-Level Interviews: III- Skip-level interviews — dialogs between a subordinate and the subordinate's supervisor's supervisor

— can be hazardous. Here's Part III of a little catalog of the hazards, emphasizing subordinate-initiated

skip-level interviews.

Pushing the "Stupid" Button

Pushing the "Stupid" Button- Some people know exactly how to lead others to feel ignorant or unintelligent. Here's a little catalog

of tactics to watch for.

Counterproductive Knowledge Workplace Behavior: II

Counterproductive Knowledge Workplace Behavior: II- In knowledge-oriented workplaces, counterproductive work behavior takes on forms that can be rare or

unseen in other workplaces. Here's Part II of a growing catalog.

Unrecognized Bullying: I

Unrecognized Bullying: I- Much workplace bullying goes unrecognized. Three reasons: (a) conventional definitions of bullying exclude

much actual bullying; (b) perpetrators cleverly evade detection; and (c) cognitive biases skew our perceptions

so we don't see some bullying as bullying.

Downscoping Under Pressure: I

Downscoping Under Pressure: I- When projects overrun their budgets and/or schedules, we sometimes "downscope" to save time

and money. The tactic can succeed — and fail. Three common antipatterns involve politics, the

sunk cost effect, and cognitive biases that distort estimates.

See also Devious Political Tactics and Devious Political Tactics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!