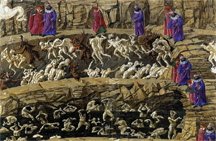

Dante Alighieri's Eighth Circle of Hell, where the souls of those who committed frauds are punished. The top half, called Bolgia 1, is reserved for panderers and seducers. The lower half, called Bolgia 2, is reserved for flatterers. Illustration titled Canto XVIII by Sandro Botticelli, dated in the 1480s. Flattery is indeed an old tactic. Image courtesy Wikimedia.

Receiving praise — or positive messages of any kind from others — about oneself generally feels good. Even wonderful. The intensity of the feeling is likely correlated with the significance of the message. Examples are compliments from one's teacher about one's work, winning an Oscar for Best Screenplay, or receiving a marriage proposal from someone you love.

As wonderful as positive messages might feel, some positive messages can be harmful or dangerous. For example, someone intent on gaining your agreement to perform an onerous or risky task might preface the request with praise for your performance on a previous task: "Rick, you so clearly demonstrated your expertise with lions last week, how about you slay this horrible dragon this week?" To persuade someone using flattery is such a common and ancient ploy that it has several names in many languages. In English, for example, to persuade using flattery is to cajole or to inveigle.

Because our responses to positive messages are almost always pleasurable, we can sometimes have difficulty distinguishing helpful positive messages from harmful or dangerous positive messages. Knowing where positive messages lie on the Helpful-to-Harmful spectrum can be advantageous to anyone engaged in workplace politics. And, one might argue, anyone who works is engaged in workplace politics.

Positive messages appear in a variety of forms. Tone and intention can be as important as content. For example, after one participant in a meeting contributes a comment to a discussion, another participant might say, "Right, I hadn't considered that possibility. Good thing you noticed that." Another possibility: after a long silence, someone might say, "Whoops. Now we're in real trouble." The former is a clear statement of appreciation. The latter can also be positive, perhaps. If the speaker is acknowledging the value of recognizing a problem, the comment is helpful. But you'd be wise to consider alternative interpretations.

The variety As wonderful as positive messages

might feel, some positive messages

can be harmful or dangerous. Learn

to distinguish flattery from praise.of forms of positive messages complicates classification. Still, an ability to recognize some of the attributes of the most harmful forms can provide a useful level of safety. In that spirit I offer the little catalog below. In what follows, I'll refer to the sender of the positive message as Author, the target of the positive message as Recipient, and witnesses to the delivery of the message as Audience.

- Indirectness

- A direct positive message is one that states clearly what attribute or action of Recipient is worthy of note. In a healthy environment, expressing appreciation of one's colleagues is commendable and constructive. Indeed, in healthy environments, such expressions can be relatively common.

- However, in environments in which delivering direct positive messages is so rare that such incidents stand out as exceptional, directness can be associated with questionable motivations. Directness in such circumstances can seem awkward, insincere, or phony. Recipients sometimes respond with skepticism, wondering what Author might be seeking now.

- Indirectness can mitigate the risk of seeming insincere. Here's a direct form (spoken at a meeting): "Evan did a great job on the Marigold risk profile." Compare this to the indirect form: "If anyone is looking for a pattern to follow for documenting risk profiles, have a look at what Evan did for Marigold." The former, the direct form, is positive, but leaves one wondering why Author mentions it, or why Author is mentioning it now. The latter, an indirect form, answers such questions pre-emptively: Author is interested in process improvement. Authors who wish to prevent Recipients from questioning Author's motivations might use indirectness to do so.

- Sincerity

- Compared to sincere positive messages, insincere positive messages are more likely to be harmful. The sincerity of a positive message is related to the extent to which it is specific and detailed about what Author found to be worthy of comment. Being specific and detailed entails a degree of risk, because Author is actually conveying two messages. The first message is the positive message about Recipient or something Recipient has done. The second message is a message about what Author finds worthy of comment. This second message can carry some risk for Author if an Audience witnesses the message delivery, because, of course, some of the Audience might disagree.

- Some Authors manage this risk by limiting the specificity and detail of their messages. Some manage risk by limiting the Audience — by delivering the message in private. The sincerity of the message is more questionable the more its Author has invested in risk management by limiting specificity, detail, or Audience.

- An example of a positive but less sincere message: "I agree with the point Sara just made about a hidden risk. And I think we can easily deal with that risk should it materialize." This message is nonspecific and lacking in detail. A more sincere version would have provided more detail about why Sara's point is important. This example also contains a contradiction, making the message even less positive than it might have been.

- Infrequency

- Authors who repeatedly deliver positive messages risk cheapening the value of those messages. An elevated frequency of positive messages from one Author could indicate that the Author is using the messages as part of a strategy of ingratiating Recipients. This is a more likely possibility if the messages relate to only one or a few Recipients, or if the messages are delivered more frequently when Author wants something from Recipient.

- Infrequent positive messages are more likely to be received as genuine, by both Recipient and Audience. Beware positive messages from someone who authors them with great frequency, especially when they're repetitious in content.

- Audience size

- As noted above, delivering positive messages in private — one-to-one — is a way for Author to limit risk of exposure to contradiction. Recipient would be well advised to treat with skepticism, even suspicion, positive messages received in private, especially if Author fails to deliver similar messages when an Audience is present and an appropriate opportunity arises. All other factors being equal, the genuineness of positive messages is likely correlated with the size or political significance of the Audience.

- Conversely, during a time when an Author is delivering a positive message to Recipient, a member of Audience might take steps to distract the attention of other members of the Audience, or otherwise interfere with Author's delivery of positive messages. When this occurs, the distracting individual might be acting out of obtuseness. Another possibility is that he or she intends to disrupt delivery of Author's message.

Positive messages feel good. That feeling can interfere with our ability to process the significance of the message by biasing us in favor of attributing benign motives to the senders of the messages. The extent to which that bias presents political risk depends on the nature of the political environment. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Workplace Politics:

Conversation Despots

Conversation Despots- Some people insist that conversations reach their personally favored conclusions, no matter what others

want. Here are some of their tactics.

Backstabbing

Backstabbing- Much of what we call backstabbing is actually just straightforward attack — nasty, unethical,

even evil, but not backstabbing. What is backstabbing?

The Utility Pole Antipattern: I

The Utility Pole Antipattern: I- Organizational processes can get so complicated that nobody actually knows how they work. If getting

something done takes too long, the organization can't lead its markets, or even catch up to the leaders.

Why does this happen?

Anticipate Counter-Communication

Anticipate Counter-Communication- Effective communication enables two parties to collaborate. Counter-communication is information provided

by a third party that contradicts the basis of agreements or undermines that collaboration.

Intentionally Misreporting Status: II

Intentionally Misreporting Status: II- When we report the status of the work we do, we sometimes confront the temptation to embellish the good

news or soften the bad news. Reporting the real situation can be so difficult, in part, because of fear,

ambition, and self-delusion.

See also Workplace Politics and Workplace Politics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!