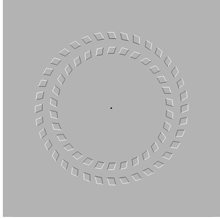

A visual illusion. While staring at the dot in the center of the image, move your head forward and back. You'll see the two rings of quadrilaterals rotate in opposite directions. They don't actually rotate at all, much less in opposite directions, but your visual system tells you that they do. Even after you're aware that this is an illusion, you can't make the illusion "go away." That is also the hallmark of cognitive biases. Even when we're aware of their effects, we can't manage to exercise unbiased judgments. To avoid the effects of a cognitive bias that affects personal judgment in a given situation, we must recruit the assistance of someone (or several someones) who aren't in that situation, and who thus aren't subject to that cognitive bias. Of course, because they could be subject to some other cognitive bias or biases, designing bias-avoidance procedures can be tricky. Image courtesy U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Google "scope creep" and you get over 10.1 million hits. Mission creep gets 15.6 million. Feature creep also gets over 20.2 million. That's pretty good for a technical concept, even if it isn't quite "miley" territory (222 million). The concept is known widely enough that anyone with project involvement has probably had first-hand experience with scope creep.

If we know so much about scope creep, why haven't we eliminated it? One simple possible answer: Whatever techniques we're using probably aren't working. Maybe the explanation is that we're psychologically challenged — that is, we, as humans, have a limited ability to detect scope creep, or to acknowledge that it's happening. If that's the case, a reasonable place to search for mechanisms to explain its prevalence is the growing body of knowledge about cognitive biases.

A cognitive bias is the tendency to make systematic errors of judgment based on thought-related factors rather than evidence. For example, a bias known as self-serving bias causes us to tend to attribute our successes to our own capabilities, and our failures to situational disorder.

Cognitive biases offer an enticing possible explanation for the prevalence of scope creep despite our awareness of it, because "erroneous intuitions resemble visual illusions in an important respect: the error remains compelling even when one is fully aware of its nature." [Kahneman 1977] [Kahneman 1979] Let's consider one example of how a cognitive bias can make scope creep more likely.

In their 1977 report, Kahneman and Tversky identify one particular cognitive bias, the planning fallacy, which afflicts planners. They The planning fallacy can lead to

scope creep because underestimates

of cost and schedule can lead

decision makers to feel that

they have time and resources

that don't actually existdiscuss two types of information used by planners. Singular information is specific to the case at hand; distributional information is drawn from similar past efforts. The planning fallacy is the tendency of planners to pay too little attention to distributional evidence and too much to singular evidence, even when the singular evidence is scanty or questionable. Failing to harvest lessons from the distributional evidence, which is inherently more diverse than singular evidence, the planners tend to underestimate cost and schedule.

But because the planning fallacy leads to underestimates of cost and schedule, it can also lead to scope creep. Underestimates can lead decision makers to feel that they have time and resources that don't actually exist: "If we can get the job done so easily, it won't hurt to append this piece or that."

Accuracy in cost and schedule estimates thus deters scope creep. We can enhance the accuracy of estimates by basing them not on singular data alone, but instead on historical data regarding organizational performance for efforts of similar kind and scale. And we can require planners who elect not to exploit distributional evidence in developing their estimates to explain why they made that choice.

In coming issues we'll examine other cognitive biases that can contribute to scope creep. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Declaring Condition Red

Declaring Condition Red- High-performance teams have customary ways of working together that suit them, their organizations,

and their work. But when emergencies happen, operating in business-as-usual mode damages teams —

and the relationships between their people — permanently. To avoid this, train for emergencies.

Toxic Projects

Toxic Projects- A toxic project is one that harms its organization, its people or its customers. We often think of toxic

projects as projects that fail, but even a "successful" project can hurt people or damage

the organization — sometimes irreparably.

The Injured Teammate: I

The Injured Teammate: I- You're a team lead, and one of the team members is very ill or has been severely injured. How do you

handle it? How do you break the news? What does the team need? What do you need?

More Obstacles to Finding the Reasons Why

More Obstacles to Finding the Reasons Why- Retrospectives — also known as lessons learned exercises or after-action reviews — sometimes

miss important insights. Here are some additions to our growing catalog of obstacles to learning.

Lessons Not Learned: II

Lessons Not Learned: II- The planning fallacy is a cognitive bias that causes us to underestimate the cost and effort involved

in projects large and small. Efforts to limit its effects are more effective when they're guided by

interactions with other cognitive biases.

See also Project Management and Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II

Coming April 30: On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: II- When we finally execute plans, we encounter obstacles. So we find workarounds or adjust the plans. But there are times when nothing we try gets us back on track. When this happens for nearly every plan, we might be working in a plan-hostile environment. Available here and by RSS on April 30.

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying

And on May 7: Subject Matter Bullying- Most workplace bullying tactics have analogs in the schoolyard — isolation, physical attacks, name-calling, and rumor-mongering are common examples. Subject matter bullying might be an exception, because it requires expertise in a sophisticated knowledge domain. And that's where trouble begins. Available here and by RSS on May 7.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenfHlRlTgqCIXkUHBTner@ChacrEuHRQPYVKkOucGfoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!